Featured articles

Latest articles

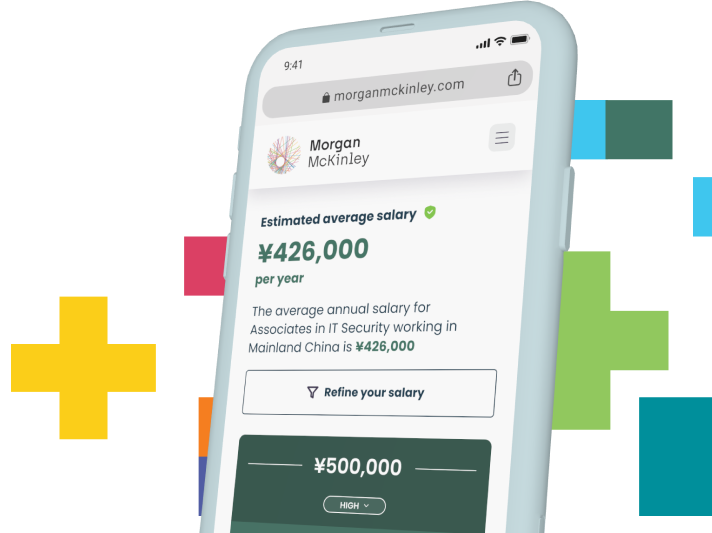

10 Of The Highest Paying Jobs In China In 2025

Using data from our 2025 Salary Guide, we have outlined some of the highest-paying jobs in China.

Key jobs in demand for 2025 in Mainland China

In our 2025 Salary Guide, we've uncovered the top roles shaping China's job market this year. Drawing insights from conversations with hiring managers…

Preparing for your interview

Prepare, Review, Evaluate, PerfectMorgan McKinley has developed a tailored approach to preparing you for interview with clients –…

Considering a career move?

If you want to progress or even move into a new industry, browse our current vacancies to find your ideal job today.

VIEW ALL JOBS

First 90 DAYS Template

Set yourself up for success in the first 90 days! Download the 90 Days template for candidates for a structured plan on setting and achieving your…

Money talks: should I put the salary in my job ad?

There’s an age-old question which divides many recruiters and key hiring decision makers: when advertising a role, should you include the salary range…

How To Build Change Capability In Your Organisation

In the midst of the impacts of COVID-19, ‘Change’ has never been more relevant. As companies feel the squeeze of slashed budgets, recruitment freezes…

5 reasons why hiring processes are putting off top…

In the complex world of hiring, finding the right balance often feels like a juggling act. You've secured additional positions and are in a rush to…

Pay and Perks: Your Winning Talent Strategy

43% of businesses outlined ‘Can’t compete on pay and benefits’ as the main reason they have lost out on hiring new talent in the last 6 months.

How to calculate a starting salary

You’ve identified that your company requires a new employee. This is an exciting time for you, the team they’ll be joining and the business as a whole…

Expect and Embrace the Challenges of Working Abroad

Working abroad is becoming popular these days for various reasons. Besides the more obvious benefits—cultural exploration, broadened network, new…

How to handle an employee’s pay rise request

One of your employees has asked for a pay rise and it’s up to you to respond. But how do you make the right decision?

How hiring temporary staff can meet your seasonal…

At certain periods throughout the year, many companies will have an increased workload that requires additional skills and people to help maximise…

The secret to switching off: Taking annual leave as a…

Research from the America’s International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans found that employees who take their annual leave are 40% more productive…

Boosting your teams’ productivity levels over summer

Summer can be a challenging time to maintain productivity in the workplace. With holidays and the lure of outdoor activities, it's no wonder that…

What To Do If A Salary Comparison Reveals You're…

Most people’s primary career motivation is to earn as much money as they can; it’s natural to strive for a higher salary as you progress through your…

How To Answer Salary Expectations Questions In The…

Knowing how to answer salary expectations questions is an important part of your job interview process. You need to be ready to respond when asked how…

3 New Recruitment Strategies Every Business Should Use

The hiring world was already changing, but now the transformation is clearer to see. New recruitment strategies, accelerated by the recent different…